Update 5/14/2015: Here is a short video that was made for the Fellow Award Ceremony.

Update 4/9/2015: A video of the interview is now available. It’s searchable via the synchronized transcript.

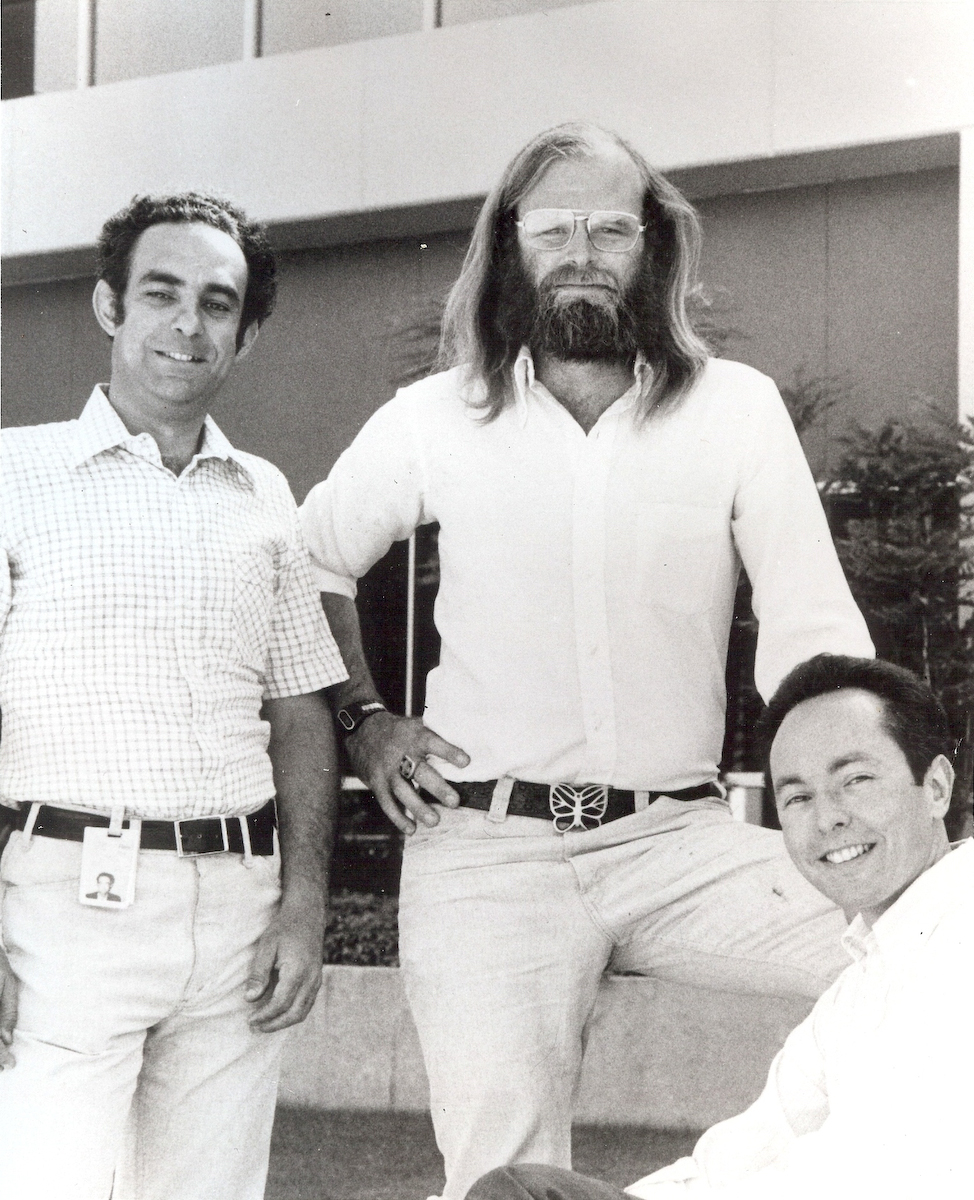

In February I had the honor of conducting an oral history of Bjarne Stroustrup for the Computer History Museum, on the occasion of his being one of three 2015 Fellow Awards Honorees (the other two being Evelyn Berezin and Charles Bachman).

Programming languages have emerged over the last fifty or so years as one of the most important tools allowing humans to convert computers from theoretical curiosities to the foundation of a new era. By inventing C++ and working tirelessly to evolve, implement, standardize, and propagate it, Bjarne has provided a foundation for software development across the gamut from systems to applications, embedded to desktop to server, commercial to scientific, across CPUs and operating systems.

C was the first systems programming language to successfully abstract the machine model of modern computers. It contained a simple but expressive set of built-in types and structuring methods (structs, arrays, and pointers) allowing efficient access to both the processor and the memory. C++ preserves C’s core model, but adds abstraction mechanisms allowing programmers to maintain efficiency and control while extending the set of types and structures.

While several of the individual ideas in C++ occurred in earlier research or programming languages, Bjarne has synthesized them into an industrial-strength language, making them available to production programmers in an coherent language. These ideas include type safety, abstract data types, inheritance, parametric polymorphism, exception handling, and more.

In addition to its synthesis of earlier paradigms, C++ pioneered a thorough and robust implementation of templates and overloading. This has enabled the field of generic programming to advance from early research to sufficient maturity for inclusion in the C++ standard library in the form of STL. Additional generic libraries for graphs, matrix algebra, image processing, and other areas are available from other sources such as Boost.

By combining efficiency and powerful abstraction mechanisms in a single language, and by achieving ubiquity across machines and operating systems, C++ has replaced a variety of more specialized languages such as C, Ada, Smalltalk, and even Fortran. Programmers need to learn fewer languages; platform providers need to invest in fewer compilers. Even newer languages such as Java and C# are clearly influenced by the design of C++.

C++ has been the major focus of Bjarne’s career, and he has had unprecedented success at incremental development of C++, keeping it stable enough for use by real programmers while gradually evolving the language to serve the broadest possible audience. As he evolved the language, Bjarne took on many additional roles in order to make C++ successful: author (books, papers, articles, lectures, and more), teacher, standardization leader, and marketing person.

Bjarne started working on C with Classes, a C++ precursor, in 1979; the first commercial release of C++ was in 1985; the first standard was in 1998, and a major revision was completed in 2011. C++ was mature enough by 1993 to be included in the second History of Programming Languages conference, and a follow-on paper focusing on standardization appeared in the third HOPL conference in 2007.

I hope you enjoy reading the oral history as much as I did interviewing Bjarne.

See also: C++ Historical Sources Archive, Dusty Decks, 11 June 2007.

Update 1/30/2016: Updated URL for C from http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/cbook/index.html to https://9p.io/cm/cs/cbook/index.html.

Several years ago I began an

Several years ago I began an